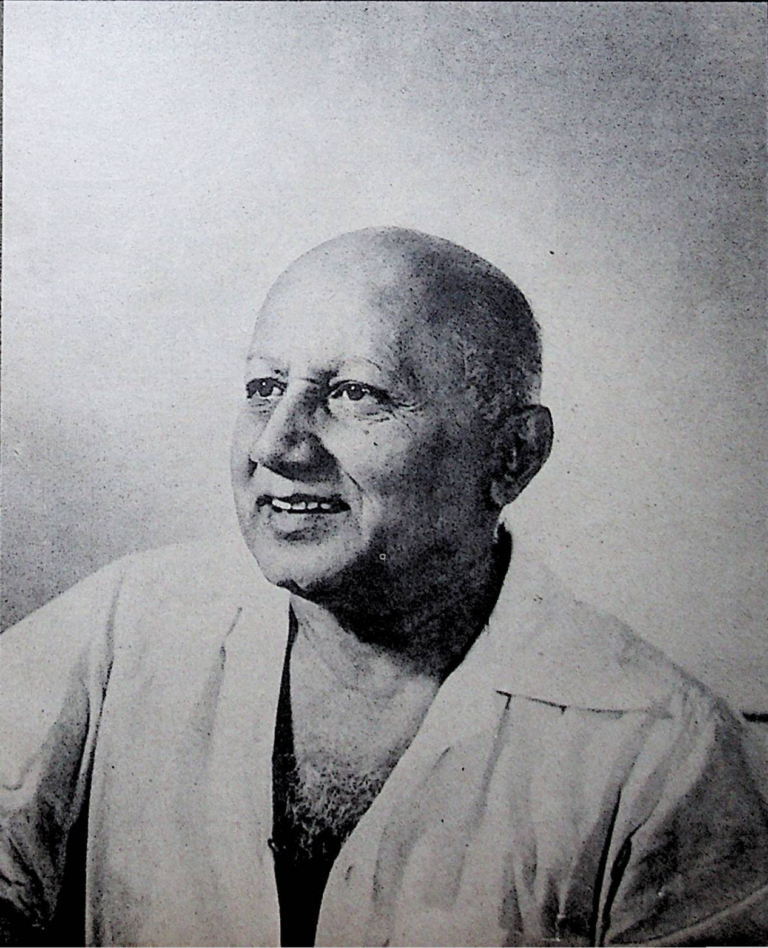

Gandharva Era

K. D. Dixit

The birth of Bal Gandharva in Maharashtra – if it is said that a master of theatrical songs emerged in India and the Gandharva era was created, it should not be considered an exaggeration. In the Indian calendar and thought, the word ‘Yug’ signifies an important period and the prominent leader of that time. Even Bhagwan seemed to want to give the assurance, “I manifest in every age.” The meaning we have given to the words Marathi stage-musical drama or Vidyarala has been nurtured, embraced, and associated with the music drama that Bal Gandharva cultivated.

Bal Gandharva was born on June 26, 1888, and Lokamanya Tilak honored Narayan as Bal Gandharva. In 1898, at just ten years old. In 1905, Bal Gandharva joined the Kirloskar music drama company – on Guru Dwadasi – and from then on, their service in theatrical art began. While performing multidimensional roles like Sharada, Malini, and Shakuntala, both their acting and singing talents flourished. In 1911, Bal Gandharva stepped onto the stage amidst thunderous applause. Thus began the Gandharva era.

The qualities and strength to become a great personality were evident at that time. On the day of the performance, early in the morning, their first daughter Hira passed away. But at that time, Narayanrao was only 23 years old – the dignified expression of self-control and dedication to the stage shown by Bal Gandharva further confirmed their greatness as a personality of the era. Later, they faced the crisis of repaying debts. Even though thousands of hands reached out to help, they bravely repaid their debts themselves. Throughout their later life, Bal Gandharva never lost courage. There is a proverb that says true great warriors treat calamity and prosperity alike. They behaved accordingly.

Flashback

After 1945, Bal Gandharva would come to the All India Radio – traveling directly by bus from Mahi to our office on Queens Road, near Goharbai’s house. At one time, they had taken a four-door Opel car. They also had a Packard for a few days. But I have never heard them express regret or sigh about it. Our acquaintance with Bal Gandharva was mainly after 1945 – by that time they had reached sixty. But when telling stories of their glory, they were cheerful, and even during their days of hardship, Bal Gandharva was never despondent. As time went on, walking became difficult for them. In a condition where they had to be moved by two people, they still recorded devotional songs from the drama. But with smiles and enthusiasm. Once, I went to visit them. I was accompanied by Sundarabai. We decided to record their voices and set off – we could not reach them – they lived on the upper floor – so it was a bit challenging – but that was all. However, when we came down, Sundarabai truly broke down in tears – “How could this happen to my elder brother?”

From Bal Gandharva, we heard many stories about their guru, Pandit Bhaskarbuwaji. While recounting them, Bal Gandharva would suddenly drift back to the glorious days of their company and become youthful, as though in a flashback. While speaking of Pandit Bhaskarbuwaji, even though they were sitting down, they would slightly rise, offer salutations, and then speak.

That Mother

In Pune, Bal Gandharva would descend at the residence of lawyer Paranjape. They were recognized as Paranjape of Ram Mandir. While at their house, we recorded an interview-like session with Bal Gandharva. It lasted almost 2 to 3 hours. Our recording machine also overheated and stopped working after such a long time. Now that tape must be in the archives of All India Radio. Many of the songs were recorded because lawyer Paranjape had a keen interest in it. The interview involved me and Bhagwan Pandit posing questions. In between, Bal Gandharva recalled their mother and said, “Well, brother, whenever I returned home from a play, she would ward off my evil eye.” Even though their father disapproved of their acting in plays, it was their mother who gave her consent. Not just consent, but she encouraged them herself. At that time, going into plays was not considered a matter of honor. But the wisdom displayed by that mother over a hundred years ago would certainly befit the mother of a great personality.

Lover-Loved One

Bal Gandharva always used to recount a lesson imparted by Pandit Bhaskarbuwaji. They repeated it again. How should the notes and rhythms be while performing? Like a lover and his beloved. This anecdote is slightly laced with a cheeky mischief. The lover says, “My love is greater than yours.”the beloved says the same. The essence of melody and rhythm should not be compromised. Then, there is a union. At that moment, no one is excessive – and so on.

In the songs and on stage of Bal Gandharva, it is the unparalleled voice of Bal Gandharva that truly matters. The praise for Bal Gandharva’s voice and songs by the late Pt. Vinayakarav Patvardhan in the special issue of ‘Ratnakar’ magazine resonates more because it comes from a great singer like him.

Listening to Bal Gandharva’s voice brings joy that raises goosebumps. This has happened many times. Nature has beautifully endowed their melody – voice. They were born in a royal swan lineage. Though Bal Gandharva may not have said it, one could say ‘Success is due to destiny, but strength comes from one’s own effort’ is something that was granted to them.

The Essence of Meaning

In the Chhandogya Upanishad, a captivating yet useful lesson is shared by the udgātṛ from the Samaveda on what and how to sing. A rivalry arose between the gods and demons in singing, and the gods began to falter one after another. This happened because the gods started singing without focusing on melody, just using words, singing with gestures and in their minds. Due to all these deficiencies, the demons began to overpower the gods. Then the gods started shedding these faults and began to sing with heartfelt, emotional devotion, and the demons were defeated. This narrative about how a singer should sing and what faults to avoid serves as an essence of meaning. This story is elaborated in the remarkable book by the late Krishnarao Mule.

A Film of Melody Lines

Bal Gandharva initiates melody with heartfelt energy. They were inherently melodious, which they beautifully polished like a diamond under the guidance of Pt. Bhaskarbuwa. Bal Gandharva created such a unique style. To say that they consciously formed a specific lineage wouldn’t align with Bal Gandharva’s modest demeanor. Bal Gandharva beautifully showcased singing and acting on stage, akin to the versatile Dhananjay. While singing ‘Prem Nach Jai’, they had a natural charm and beauty. Their attire – simple black yet sheer and delicate, with a determined yet poignant Rukmini figure, came to life. When they sang, the astonishing strength of their melody would leave impressions on one’s heart and memory. Listening to Bal Gandharva’s compositions or ‘Manas ka Badhirave’ or ‘Bhup Sare Tava Kanhe Sukha An’ would evoke a cinematic experience of just melodies – of helplessness – of despair. In contrast, the joyous essence from ‘Ajji Radha Bala’ or the grandeur from ‘Thaat Samaricha Davi Nat’ inspired us as well.

Creating Their Own Style

Bal Gandharva harmonized classical music style and acting into a single entity. This became a distinct style of the Bal Gandharva era – a significant presence on the Marathi stage. Musical theater came to be regarded as a unique blend of music and drama. Late Govindrao Tenbe, a collaborator in Bal Gandharva’s theater, a star-actor, and a music expert in their contemporary musical scene observed in his book ‘Maza Sangeet Vyasang’ that the specific style in Gandharva’s theater spread widely across Maharashtra… There is no doubt that all credit for this spread of singing goes solely to Bal Gandharva. According to Mr. Tenbe, had Bal Gandharva focused on ‘Swayanvara’ rather than ‘Ekach Pyala’, the public would have developed a taste for higher music. While there was a dedication to classical music, it stands to reason that Bal Gandharva’s goal was indeed to elevate the level of music.

During the Bal Gandharva era, from 1911 to 1962, those who contributed their unique flair to Marathi theater music were Keshavrao Bhosale, Vyan. Ba. Pendharkar, and Ma. Dinanath. Others shone brightly, but none left a lasting impression of their own. Keshavrao Bhosale had a brief tenure. Pendharkar’s distinct style was real, but except for his sons Bhalkeshwar and Damle, no one adopted it. Ma. Dinanath was indeed a talented singer, though they had no specific style of acting. However, their singing did not establish a tradition. There wasn’t one to establish either. They were artists of wisdom, ‘In every moment there is a newness.’ Only Vasantrao Deshpande recognized Ma. Dinanath. However, the Balwant music troupe did not have their own plays, which caused the tradition to fade away. But Bal Gandharva, on the other hand, adorned plays with decoration, musical accompaniment,Natana created their own style by honoring actors and sincerely worshiping music and drama. Govindrao Tembe proudly states about them, “Bal Gandharva possessed the enchanting beauty of voice, the display of the face, and the charm of femininity—all these qualities.

It seems that Bal Gandharva’s singing appears simple, but it is not so easy to sing after one actually tries. The innate understanding of rhythm and the meticulously crafted effort taken from Pandit Bhaskarbuwa allowed Bal Gandharva to start using the embellishments of rhythm and melody as effortlessly as one might use flowers in their hair. Their exceptional artistry has attained the highest level of excellence as described in ‘Yato Vacho Nivartante’.

The contribution of Gandharva

Every role in Gandharva’s theater has its own distinct place. Thus, the music in each play and the understanding of each role have become interdependent. In a special edition of ‘Ratnakar,’ when audiences were asked which role of Bal Gandharva was most beloved, they ranked Sindhu at the forefront. Opinions came in like Sindhu – 2052 and Rukmini 1301. This means that viewers valued Bal Gandharva’s acting more than the music. Because the songs in ‘Ekch Pyala’ seem plain compared to the glorious songs of ‘Swayamvara’.

After 1952, during Bal Gandharva’s later years, we were very close to them. At that time, there was an artistic awakening within them. The theater group was suggested to be revived. Vinayakrao Patwardhan was singing in Delhi, and they were contacted for support to revive the theater group.

Bal Gandharva recorded all the songs from the musical plays for Akashvani, plotting them into a seven-minute timeframe. For this, he had to work hard first, accompanied by Mr. Dinkarrao Amabal on the organ, and then record post 11 PM. Because all those songs ended up being recorded in a ditch, nothing remained. This was a major disservice. But even today, Bal Gandharva’s singing remains enjoyable, exemplary,

and personal for listeners. This is the work of that epoch-making individual. Once, Ravi Shankar told me, your classical music feels different from the North. It feels like it should be called Maharashtra’s classical music. In this Maharashtrian-ness, there is a significant aspect of theatrical music. And in that theatrical music, Gandharva’s music plays a primary role—Mahatma Gandhi gave khadi caps to Congress members, and they became a symbol of recognized patriotism. Similarly, musical spaces and nuances from Bal Gandharva’s repertoire began to appear in theatrical music, and experts started to say, this is Gandharva’s gift!

Bal Gandharva was tired, but their spirit was unwavering. The subject of life, undying drama never left their mind. Their popularity remained just like before. At our home, their song was fixed for my sister’s wedding. In truth, we were filled with joy the moment they agreed. Because on that day in Pune, it was raining heavily. But if Gandharva was singing, that was a golden opportunity in our lives. My brother requested a chair at the station. Once it was known for whom, the porters started arguing among themselves about who would pick up the chair. When Gandharva’s carriage arrived, the porters rushed saying, Maharaj has come, Maharaj has come. When a large carriage was seen outside, even the carriage driver got down to help Gandharva up with great excitement. No one took any money. On the contrary, they bowed to Gandharva with tears in their eyes.

Those Moments…

Bal Gandharva fell ill and had lost consciousness in the hospital. The people around were singing bhajans. I could not bear to witness that scene. Somehow, I returned home. At that time, I was in Bangalore. I had come for a holiday and returned after this darshan. I left the hospital with an apprehension of what would happen. During the 24-hour journey from Bangalore, I was drawing moments of our devotion to Bal Gandharva like beads on a garland.

After 1945, our daily meetings with them started happening at Akashvani. Thanks to our colleague Sitakant Lad, Gandharva appeared on Akashvani. Bal Gandharva immersed themselves with us to such an extent that sometimes they would come and sit in program meetings. Some of our colleagues did not even have sufficient idea that this epoch-making individual was sitting next to them, charming millions of connoisseurs in Maharashtra with their sweet voice. During that time, the smooth jugalbandi of Sundarabai and Bal Gandharva was in full swing. At one program, Sundarabai read out loud wearing a large pair of glasses, while Bal Gandharva had a constantly slipping nose glasses. One was a master of acting; the other, a queen of lavani. Bal Gandharva came home for dinner. They sang a song at home.Master Krishna Rao had arrived at that time. The bhajan ‘Run, Vithu, now, do not be slow’ was sung by Bal Gandharva with such flair, such fervor, and devotion that everyone was completely entranced. Master Krishna Rao even hugged him.

I remained restless all night and disembarked in Bangalore in the morning. Sad, lost.

Pandit Mallikarjun’s singing was scheduled for the morning. I was, of course, going. That would also lessen the shadow of Gandharva’s illness.

I woke up in the morning. As usual, I turned on the radio, and finally learned from the Hindi news that Bal Gandharva had passed away. I felt utterly alone. The other people in the hotel didn’t seem to care about this. I expressed my sorrow and got to work. I even forgot about Pandit Mansoor’s singing. Our assistant, Mr. Bhushanuramath, was there, and I called him. I had informed him the day before. The news had also appeared in the Kannada newspapers of Bangalore. It was at that moment that I understood Gandharva’s greatness even more. The Kannada audience in Bangalore had immense love and deep reverence for Gandharva’s theatrical singing.

We went to Mr. Gubbi Veeranna’s house. His well-formed daughter was performing excellent dance. I had already been introduced. Mr. Gubbi Veeranna is a significant figure in the Kannada theater scene. The affluent theatre troupe. He told a tale that in one of his plays, they brought an elephant on stage. At one time, Gandharva’s company and their company performed together in Hubli. They would watch each other’s plays. His wife was also in the play. I went to him while he was singing wonderfully.

He was overwhelmed by Gandharva’s death. Both of them recorded their tributes. And his wife recorded a Kannada song from their play. To the tune of ‘Truth speaks, Oh Lord’. I met another couple of knowledgeable people and paid my respects. But the most heartfelt words came from the famous novelist A. N. Krishnarao. He referred to Gandharva as the emperor of the theater world and provided excellent commentary on many of his plays. He concluded with ‘Very great, very great’.

Pandit Mallikarjun was waiting. Two tamburas were resonating. Two apprentice girls sat on the tamburas. ‘What’s the delay?’ Panditji asked, and I staggered in disbelief. Panditji had no idea. I managed to say, ‘Gandharva is gone. Yesterday.’ –

Pandit Mallikarjun immediately spread his arms wide. Over the tambura – shaking his head slowly, he said – “Brother, the melody is gone.” He was just shaking his head. Everyone was silent. Panditji held me by the hand and made me sit down. The others were also aware of our distress. They understood.

Pandit Mallikarjun suddenly lifted his hands from the tambura. The tambura gave a note, and Panditji played a vilambit ‘shadja’. Just like Bal Gandharva’s ‘shadja’, Panditji’s ‘shadja’ is a miraculous wonder. The resonance of the tambura – its sound – and Mansoor’s sixth note – one color, one essence, one unity. The good vilambit resonated until the shadja was reverberating.

One melody maestro paid homage to another melody maestro. And our Gandharva era came to an end.